What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Wellness?

It is increasingly apparent that employers approach to wellness needs a fresh approach. The current model is based on a series of assumptions which have all proven to be incorrect: first, that the majority of costs are due to a set of conditions brought about by lifestyle choices; second, that if people complete a health risk appraisal (HRA) and then work with a 1-800 health coach they will change lifestyle behaviors, become healthier; third, that using financial incentives to increase participation will result in better outcomes; and fourth, that the lowering of medical costs will be greater than the spending on the wellness programs. A final assumption is that this approach to well-being will be a satisfier for employees and a tool for recruitment and retention.

As logical as these assumptions are, over ten years of experience and evidence have challenged every one of them.

It turns out that only about 20% of health spending in a population of working adults is driven by conditions that are addressed by increasing exercise, weight loss and smoking cessation (a much higher percent of cost is linked in the Medicare population). For the majority of people HRA’s and a remote health coach do not make lifestyle habits that have always been very, very difficult to change any less so. While about 10% of people seem to have lasting improvement, the number of people participating in programs remains at a stubborn 15-20%. In addition employee turnover means that for a substantial number of employees an investment made today by Employer A will pay off years from now for a new Employer B. All this math leads to an optimistic savings of under $50/employee, far below the $600 average cost per employee for wellness programs that a recent National Business Group on Health survey revealed. And worst yet, increasing the amount of financial incentive to increase participation looks like it is alienating employees, leading them to question whether their personal health data is secure and further question whether their employer’s intense interest in their personal habits is consistent with an employer-employee relationship that they signed up for. The unintended consequence is the erosion of the employee satisfaction that these programs are supposed to deliver.

How did we get to this place? Looking back, it appears that the experts who are ‘true believers’ in health and wellness led employers astray by over-estimating the percent of spending driven by lifestyle behaviors and under-estimating how difficult it is to change these behaviors. The enthusiasts drew on a limited set of data and unproven theories to make a case that has simply not stood up. However, there is real momentum among employers and employees to have the workplace be part of a broader effort to make people healthier. I think by changing our framework about what we are talking about when we talk about wellness, this momentum can be used to advance employee health and job satisfaction.

WHAT WE NEED TO DO: Ihave spent the last several months looking at successful models of change and talking to employees about what wellness means to them. A new approach, Wellness 2.0, is based on these findings:

Sustainable Change: Smoking cessation is the best story we have of sustainable change; smoking rates have decreased from over 40% of the population in the 1960’s to less than 20% today. It turns out that a “three-legged stool” approach, in which all three legs are necessary, best explains the success:

LEG 1: an external environment that provides a positive context for change

LEG 2: intrinsic motivation accompanied by tools that make change easier

LEG 3: incentives that make change financially advantageous

In the smoking example, the external environment had two pieces, one was the ‘big’ environment of our culture as a whole and the other the ‘more local’ environment of our everyday lives. As evidence accumulated that tobacco use led to serious illness, it became less ‘cool’ to smoke and more acceptable to think of smokers as undesirable (“kissing a smoker is like licking an ashtray”). In the ‘local’ external environment it simply became more difficult to smoke, e.g. no smoking on airplanes, restaurants and worksites. For LEG 2, intrinsic motivation to change was enhanced by medications like Nicorette gum and Chantix, as well as by behavioral modification programs. Finally, the increase in taxes on cigarettes (a one-pack per day smoker spent $350 in 1980 vs. $2500 today) and the smoking surcharge that a majority of employers have imposed provided a powerful financial incentive (LEG 3 of the stool).

As we have witnessed with exercise and obesity, however, in the absence of all three legs of the stool working simultaneously success is very uncommon.

Voice of the employee: it turns out that there is a substantial disconnect between what employees mean by wellness and what employers have been offering. Employees do not view wellness as naturally connected to benefits; they see the latter as an annual insurance choice or something the minority of them need if they run into a healthcare issue. Wellness on the other hand is part of their daily life. Every day there are multiple decisions about what to eat, how to get motivated to exercise, whom to turn to with issues of stress etc. Employees are interested in living a healthy lifestyle but in their view stress is as or more important than diet and exercise. They look to employers to not add stress to their lives and to offer them jobs in which they have a sense of control. Optimally they want a workplace environment that enhances their intrinsic motivation and makes it easier to make the right choices. Finally, tying negative financial incentives to lack of participation in wellness is increasingly looking like a source of resentment rather than motivation.

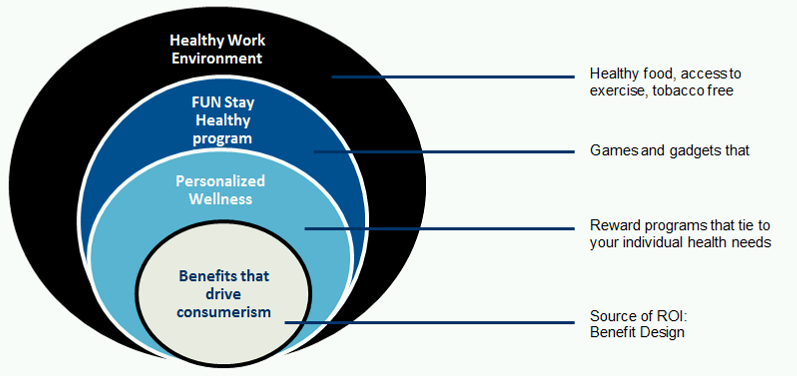

WELLNESS 2.0: It is time to transform the model. The schematic below establishes two new principles: first, benefit design changes that drive consumerism and not wellness programs are the source of savings; and second, the design of wellness programs should be based wholly on the “voice-of-the-employee-as-customer”, recognizing that these programs represent just on leg of the three-legged stool. Applying these two principles a transformed program would adhere to the following guidelines:

- Customize – meet employees where they are: the majority employees do not view a HRA + biometrics and availability of a 1-800 health coach as something that meets their wellness needs. Their view of wellness is better described as well-being’ and is quite varied: many are already involved in wellness activities in their communities and others have adopted new technologies to motivate them to change (e.g., Fitbits). A customized approach would move from a one-size-fits-all approach to one that offers a very wide array of wellness activities and allows the employee to choose the one consistent with their interest.

- Gamify – make it fun: employees are more likely to engage and view wellness offerings as satisfiers if they are fun. Doing an HRA and working with a health coach is effective for some employees but for many it is like have to take their bad tasting medicine. Employees have communicated a preference for games, raffles, friendly competitions, etc. It is up to employers to deliver these offerings to employees.

- Incentivize (carrots only): despite evidence that sticks may be more effectible than carrots in driving participation employees are making it clear in surveys (and in the experience at call centers that are using this approach) that avoiding a penalty may increase participation but at the cost of discouraging rather than increasing intrinsic motivation.

- No ROI: there is plenty of money to be saved by making employees better consumers of care and benefit designs that drive consumerism are the source of the savings. Looking to wellness programs to deliver ROI is both futile (they don’t have a positive ROI) and limiting. In the Wellness 2.0 model, the ROI should be calculated from the overall efforts in healthcare, integrating benefit design savings and wellness and other programs, Freeing wellness programs from being a source of savings makes it easier to reshape them to meet employee’s needs.

- Healthy Worksite: to date, wellness programs have focused on the intrinsic motivation and financial incentive legs of three-legged stool necessary for change. Without a change in the external environment, however, expectations for sustainable change are unrealistic. Employers are uniquely positioned to make the work environment a key facilitator of change by adopting certain worksite policies and practices that make it easier for employees to make the healthy choices. For example, if a worksite offers and subsidizes good-tasting healthy food so it is the more economical choice employees will eat healthier. As part of the Wellness 2.0 model Equity Healthcare will develop a set of standards and a self-audit tool which companies can use to measure how healthy their worksites are.

Moving to a Wellness 2.0 model is consistent with how employers operate on their commercial sides: listen to customers, learn from experience and embrace rather than resist innovation. Modifying the Change and ROI frameworks in which wellness programs operate will lead to more effective programs that satisfy employees to a much greater extent than today’s model. A Wellness 2.0 approach will require new suppliers and changes in worksite policies and practices. But as it becomes increasingly clear that employers are going to stay the course in funding healthcare for their employees, moving away from a model that’s simply not working to one based on common sense and evidence seems the smart way to go.